Borobudur is a ninth-century Mahayana Buddhist monument near Magelang,

Central Java, Indonesia. The monument comprises six square

platforms topped by three circular platforms, and is decorated with

2,672 relief

panels and 504 Buddha statues. A main dome, located at the center of the top platform, is surrounded

by 72 Buddha statues seated inside perforated stupa.

The monument is both a shrine to the Lord Buddha and a place for Buddhist pilgrimage.

The journey for pilgrims begins at the base of the monument and follows

a path circumambulating the monument while

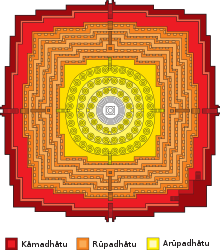

ascending to the top through the three levels of Buddhist cosmology, namely Kāmadhātu (the world of desire), Rupadhatu

(the world of forms) and Arupadhatu (the world of formlessness).

During the journey the monument guides the pilgrims through a system of

stairways and corridors with 1,460 narrative relief panels on the wall

and the balustrades.

Evidence suggests Borobudur was abandoned following the fourteenth

century decline of Buddhist and Hindu kingdoms in Java, and the Javanese conversion to Islam. Worldwide knowledge of its existence was sparked in 1814 by Sir Thomas

Stamford Raffles, the then British ruler of Java, who was advised of its location by

native Indonesians. Borobudur has since been preserved through several

restorations. The largest restoration project was undertaken between

1975 and 1982 by the Indonesian

government and UNESCO, following which the monument was listed as a

UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Borobudur is still used for pilgrimage; once a year Buddhists in

Indonesia celebrate Vesak at the monument, and

Borobudur is Indonesia's single most visited tourist attraction.

Etymology

In Indonesian, ancient temples are known as

candi; thus "Borobudur Temple" is

locally known as Candi Borobudur. The term candi is also

used more loosely to describe any ancient structure, for example gates

and bathing structures. The origins of the name Borobudur however

are unclear,

although the original names of most ancient Indonesian temples are no

longer known.

The name Borobudur was first written in Sir Thomas Raffles' book on Javan

history.

Raffles wrote about a monument called borobudur, but there are

no older documents suggesting the same name.

The only old Javanese manuscript that hints at the monument as a

holy Buddhist sanctuary is Nagarakretagama, written by Mpu

Prapanca in 1365.

The name 'Bore-Budur', and thus 'BoroBudur', is thought to have been

written by Raffles in English grammar to mean the nearby village of Bore; most candi

are named after a nearby village. If it followed Javanese language, the monument should have been named

'BudurBoro'. Raffles also suggested that 'Budur' might correspond to the

modern Javanese word Buda ('ancient') – i.e., 'ancient Boro'. However, another archaeologist suggests the second component of the

name ('Budur') comes from Javanese term bhudhara (mountain).

Karangtengah inscription dated 824 mentioned about the sima

(tax free) lands awarded by Çrī Kahulunan (Pramodhawardhani) to ensure

the funding and maintenance of a Kamūlān called Bhūmisambhāra.

Kamūlān itself from the word mula which means 'the place

of origin', a sacred building to honor the ancestors, probably the ancestors of the Sailendras.

Casparis suggested that Bhūmi Sambhāra Bhudhāra which in Sanskrit

means "The mountain of combined virtues of the ten stages of Boddhisattvahood", was the original name of

Borobudur.

Location

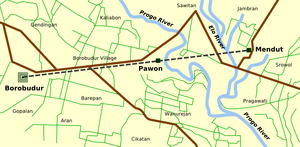

Approximately 40 kilometers (25 mi) northwest of Yogyakarta, Borobudur is located in an

elevated area between two twin volcanoes, Sundoro-Sumbing

and Merbabu-Merapi, and two rivers, the Progo and the Elo.

According to local myth, the area known as Kedu

Plain is a Javanese 'sacred' place

and has been dubbed 'the garden of Java' due to its high agricultural fertility.

Besides Borobudur, there are other Buddhist and Hindu

temples in the area, including the Prambanan

temples compound. During the restoration in the early 1900s, it was

discovered that three Buddhist temples in the region, Borobudur, Pawon and Mendut,

are lined in one straight line position.

It might be accidental, but the temples' alignment is in conjunction

with a native folk tale that a long time ago, there was a

brick-paved road from Borobudur to Mendut with walls on both sides. The

three temples (Borobudur–Pawon–Mendut) have similar architecture and

ornamentation derived from the same time period, which suggests that

ritual relationship between the three temples, in order to have formed a

sacred unity, must have existed, although exact ritual process is yet

unknown.

Unlike other temples, which were built on a flat surface, Borobudur

was built on a bedrock hill, 265 m (869 ft) above sea level and 15 m (49 ft) above

the floor of the dried-out paleolake.

The lake's existence was the subject of intense discussion among

archaeologists in the twentieth century; Borobudur was thought to have

been built on a lake shore or even floated on a lake. In 1931, a Dutch

artist and a scholar of Hindu and Buddhist architecture, W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp, developed a theory that Kedu Plain

was once a lake and Borobudur initially represented a lotus flower floating on the lake.

Lotus flowers are found in almost every Buddhist work of art, often

serving as a throne for buddhas and base for stupas. The architecture of

Borobudur itself suggests a lotus depiction, in which Buddha postures

in Borobudur symbolize the Lotus

Sutra, mostly found in many Mahayana

Buddhism (a school of Buddhism widely spread in the east

Asia region) texts. Three circular platforms on the top are also

thought to represent a lotus leaf.

Nieuwenkamp's theory, however, was contested by many archaeologists

because the natural environment surrounding the monument is a dry land.

Geologists, on the other hand, support Nieuwenkamp's view, pointing

out clay

sediments found near the site.

A study of stratigraphy, sediment and pollen

samples conducted in 2000 supports the existence of a paleolake

environment near Borobudur,

which tends to confirm Nieuwenkamp's theory. The lake area fluctuated

with time and the study also proves that Borobudur was near the lake

shore circa thirteenth and

fourteenth century. River flows and volcanic

activities shape the surrounding landscape, including the lake. One

of the most active volcanoes in Indonesia, Mount Merapi, is in the

direct vicinity of Borobudur and has been very active since the Pleistocene.

History

Construction

There is no written record of who built Borobudur or of its intended

purpose.

The construction time has been estimated by comparison between carved

reliefs on the temple's hidden foot and the inscriptions commonly used in royal charters

during the eight and ninth centuries. Borobudur was likely founded

around 800 AD.

This corresponds to the period between 760–830 AD, the peak of the Sailendra

dynasty in central Java,

when it was under the influence of the Srivijayan

Empire. The construction has been estimated to have taken 75 years

and been completed during the reign of Samaratungga

in 825.

There is confusion between Hindu

and Buddhist

rulers in Java

around that time. The Sailendras were known as ardent followers of Lord

Buddha, though stone inscriptions found at Sojomerto suggest they may

have been Hindus.

It was during this time that many Hindu and Buddhist monuments were

built on the plains and mountain around the Kedu Plain. The Buddhist

monuments, including Borobudur, were erected around the same time as the

Hindu Shiva

Prambanan

temple compound. In 732 AD, the Shivaite King Sanjaya

commissioned a Shivalinga sanctuary to be

built on the Ukir hill, only 10 km (6.2 miles) east of Borobudur.

Construction of Buddhist temples, including Borobudur, at that time

was possible because Sanjaya's immediate successor, Rakai Panangkaran, granted his

permission to the Buddhist followers to build such temples.

In fact, to show his respect, Panangkaran gave the village of Kalasan to the Buddhist community, as is written

in the Kalasan Charter dated 778 AD.

This has led some archaeologists to believe that there was never

serious conflict concerning religion in Java as it was possible for a

Hindu king to patronize the establishment of a Buddhist monument; or for

a Buddhist king to act likewise.

However, it is likely that there were two rival royal dynasties in Java

at the time—the Buddhist Sailendra and the Saivite Sanjaya—in which the latter triumphed

over their rival in the 856 battle on the Ratubaka

plateau.

This confusion also exists regarding the Lara Jonggrang temple at the Prambanan

complex, which was believed that it was erected by the victor Rakai

Pikatan as the Sanjaya dynasty's reply to Borobudur,

but others suggest that there was a climate of peaceful coexistence

where Sailendra involvement exists in Lara Jonggrang.

Abandonment

Borobudur lay hidden for centuries under layers of volcanic

ash and jungle growth. The facts behind its abandonment remain a

mystery. It is not known when active use of the monument and Buddhist

pilgrimage to it ceased. Somewhere between 928 and 1006, the center of

power moved to East Java region and a series of volcanic

eruptions took place; it is not certain whether the latter influenced

the former but several sources mention this as the most likely period of

abandonment.

Soekmono (1976) also mentions the popular belief that the temples were

disbanded when the population converted to Islam in the

fifteenth century.

The monument was not forgotten completely, though folk stories

gradually shifted from its past glory into more superstitious beliefs associated with bad luck

and misery. Two old Javanese chronicles (babad)

from the eighteenth century mention cases of bad luck associated with

the monument. According to the Babad Tanah Jawi (or the History

of Java), the monument was a fatal factor for a rebel who revolted

against the king of Mataram in 1709.

The hill was besieged and the insurgents were defeated and sentenced to

death by the king. In the Babad Mataram (or the History of the

Mataram Kingdom), the monument was associated with the misfortune of the

crown prince of the Yogyakarta Sultanate in 1757.

In spite of a taboo against visiting the monument, "he took what is

written as the knight who was captured in a cage (a statue in one

of the perforated stupas)". Upon returning to his palace, he fell ill

and died one day later.

Rediscovery

Following the Anglo-Dutch Java War, Java was under

British administration from 1811 to 1816. The appointed governor was

Lieutenant Governor-General Thomas Stamford

Raffles, who took great interest in the history of Java. He

collected Javanese antiques and made notes through contacts with local

inhabitants during his tour throughout the island. On an inspection tour

to Semarang

in 1814, he was informed about a big monument deep in a jungle near the

village of Bumisegoro.

He was not able to make the discovery himself and sent H.C. Cornelius, a

Dutch engineer, to investigate.

The first photograph of Borobudur by Isidore van Kinsbergen (1873) after

the monument was cleared up.

In two months, Cornelius and his 200 men cut down trees, burned down

vegetation and dug away the earth to reveal the monument. Due to the

danger of collapse, he could not unearth all galleries. He reported his

findings to Raffles including various drawings. Although the discovery

is only mentioned by a few sentences, Raffles has been credited with the

monument's recovery, as one who had brought it to the world's

attention.

Hartmann, a Dutch administrator of the Kedu region, continued

Cornelius' work and in 1835 the whole complex was finally unearthed. His

interest in Borobudur was more personal than official. Hartmann did not

write any reports of his activities; in particular, the alleged story

that he discovered the large statue of Buddha in the main stupa.

In 1842, Hartmann investigated the main dome although what he

discovered remains unknown as the main stupa remains empty.

An 1895 hand tinted lantern slide

of a guardian statue at Borobudur (Photograph by William Henry Jackson)

The Dutch East Indies government then

commissioned F.C. Wilsen, a Dutch engineering official, who studied the

monument and drew hundreds of relief sketches. J.F.G. Brumund was also

appointed to make a detailed study of the monument, which was completed

in 1859. The government intended to publish an article based on Brumund

study supplemented by Wilsen's drawings, but Brumund refused to

cooperate. The government then commissioned another scholar, C. Leemans,

who compiled a monograph based on Brumund's and Wilsen's sources.

In 1873, the first monograph of the detailed study of Borobudur was

published, followed by its French translation a year later.

The first photograph of the monument was taken in 1873 by a Dutch-Flemish engraver, Isidore van Kinsbergen.

Appreciation of the site developed slowly, and it served for some

time largely as a source of souvenirs and income for "souvenir hunters"

and thieves. In 1882, the chief inspector of cultural artifacts

recommended that Borobudur be entirely disassembled with the relocation

of reliefs into museums due to the unstable condition of the monument.

As a result, the government appointed Groenveldt, an archeologist, to undertake a thorough

investigation of the site and to assess the actual condition of the

complex; his report found that these fears were unjustified and

recommended it be left intact.

Contemporary events

Following the major 1973 renovation funded by UNESCO,

Borobudur is once again used as a place of worship and pilgrimage. Once a year, during the full

moon in May or June, Buddhists in Indonesia observe Vesak (Indonesian: Waisak) day commemorating the birth, death, and

the time when Siddhārtha Gautama attained the highest

wisdom to become the Buddha Shakyamuni. Vesak is an official national holiday in Indonesia

and the ceremony is centered at the three Buddhist temples by walking

from Mendut

to Pawon

and ending at Borobudur.

The monument is the single most visited tourist attraction in Indonesia. In 1974, 260,000

tourists of whom 36,000 were foreigners visited the monument.

The figure hiked into 2.5 million visitors annually (80% were domestic

tourists) in the mid 1990s, before the

country's economy crisis.

Tourism development, however, has been criticized for not including the

local community on which occasional local conflict has arisen. In 2003, residents and small businesses around Borobudur organized

several meetings and poetry protests, objecting to a provincial

government plan to build a three-story mall complex, dubbed the 'Java

World'.

On 21 January 1985, nine stupas were badly damaged by nine bombs.

In 1991, a blind Muslim preacher, Husein Ali Al Habsyie, was sentenced

to life imprisonment for masterminding a series of

bombings in the mid 1980s including the temple attack.

Two other members of a right-wing extremist

group that carried out the bombings were each sentenced to 20 years

in 1986 and another man received a 13-year prison term. On 27 May 2006,

an earthquake of 6.2 magnitude on the Richter scale struck the south coast

of Central Java. The event had caused severe damage around the region

and casualties to the nearby city of Yogyakarta,

but Borobudur remained intact.

On 28 August 2006 the Trail of Civilizations symposium was held in

Borobudur under the auspices of the governor of Central Java and the

Indonesian Ministry of Culture and Tourism, also present the

representatives from UNESCO and predominantly Buddhist nations of

Southeast Asia, such as Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam

and Cambodia.

Climax of the event was the "Mahakarya Borobudur" ballet performance in

front of the temple of Borobudur. It was choreographed to feature

traditional Javanese dancing, music and costumes, and tell the history

about the construction of the Borobudur. After the symposium, the

Mahakarya Borobudur ballet is performed several times, especially during

annual national Waisak commemoration at Borobudur

attended by Indonesian President.

UNESCO identified three specific areas of concern under the present

state of conservation: (i) vandalism by visitors; (ii) soil erosion in

the south-eastern part of the site; (iii) analysis and restoration of

missing elements.

The soft soil, the numerous earthquakes and heavy rains lead to the

destabilization of the structure. Earthquakes are by far the most

contributing factors, since not only stones fall down and arches

crumble, but the earth itself moves can move in waves, further

destroying the structure.[37]

The increasing popularity of the stupa brings in many visitors, most of

whom are from Indonesia. Despite warning signs on all levels not to

touch anything, the regular transmission of warnings over loudspeakers

and the presence of guards, vandalism on reliefs and statues is a common

occurrence and problem, leading to further deterioration. As of 2009,

there is no system in place to limit the number of visitors allowed per

day, or to introduce mandatory guided tours only.

Architecture

Borobudur ground plan took form of a Mandala.

Borobudur is built as a single large stupa, and

when viewed from above takes the form of a giant tantric

Buddhist mandala, simultaneously representing the

Buddhist cosmology and the nature of mind.

The foundation is a square, approximately 118 meters (387 ft) on each

side. It has nine platforms, of which the lower six are square and the upper three are circular.

The upper platform features seventy-two small stupas surrounding one

large central stupa. Each stupa is bell-shaped and pierced by numerous

decorative openings. Statues of the Buddha sit inside the pierced enclosures.

Approximately 55,000 cubic metres (72,000 cu yd) of stones were taken

from neighbouring rivers to build the monument. The stone was cut to size, transported to the site and laid without mortar. Knobs, indentations and dovetails were used to form joints between stones. Reliefs

were created in-situ after the building

had been completed. The monument is equipped with a good drainage

system to cater for the area's high stormwater run-off. To avoid

inundation, 100 spouts are provided at each corner with a unique carved gargoyles

in the shape of giants or makaras.

Borobudur differs markedly with the general design of other

structures built for this purpose. Instead of building on a flat

surface, Borobudur is built on a natural hill. The building technique

is, however, similar to other temples in Java. With no inner space as in

other temples and its general design similar to the shape of pyramid,

Borobudur was first thought more likely to have served as a stupa,

instead of a temple.

A stupa is intended as a shrine for

the Lord Buddha. Sometimes stupas were built only as devotional symbols

of Buddhism. A temple, on the other hand, is used as a house of deity and

has inner spaces for worship. The complexity of the monument's

meticulous design suggests Borobudur is in fact a temple. Congregational

worship in Borobudur is performed by means of pilgrimage. Pilgrims were

guided by the system of staircases and corridors ascending to the top

platform. Each platform represents one stage of enlightenment. The path that

guides pilgrims was designed with the symbolism of sacred knowledge

according to the Buddhist cosmology.

Little is known about the architect Gunadharma.

His name is actually recounted from Javanese legendary folk tales

rather than written in old inscriptions. The basic unit measurement he

used during the construction was called tala, defined as the

length of a human face from the forehead's hairline to the tip of the

chin or the distance from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the middle

finger when both fingers are stretched at their maximum distance.

The unit metrics is then obviously relative between persons, but the

monument has exact measurements. A survey conducted in 1977 revealed

frequent findings of a ratio of 4:6:9 around the monument. The architect

had used the formula to lay out the precise dimensions of Borobudur.

The identical ratio formula was further found in the nearby Buddhist

temples of Pawon and Mendhut. Archeologists conjectured the purpose of

the ratio formula and the tala dimension has calendrical,

astronomical and cosmological themes, as of the case in other Hindu and

Buddhist temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia.

The main vertical structure can be divided into three groups: base

(or foot), body, and top, which resembles the three major division of a

human body.

The base is a 123x123 m (403.5x403.5 ft) square in size and 4 meters

(13 ft) high of walls.

The body is composed of five square platforms each with diminishing

heights. The first terrace is set back 7 meters (23 ft) from the edge of

the base. The other terraces are set back by 2 meters (7 ft), leaving a

narrow corridor at each stage. The top consists of 3 circular

platforms, with each stage supporting a row of perforated stupas,

arranged in concentric circles. There is one main dome at the

center; the top of which is the highest point of the monument

(35 meters (115 ft) above ground level). Access to the upper part is

through stairways at the centre of each 4 sides with a number of arched

gates, watched by a total of 32 lion statues. The gates is adorned with Kala's head carved on top center of each portals with Makaras projecting from each sides.

This Kala-Makara style is commonly found in Javanese temples portal.

The main entrance is at the eastern side, the location of the first

narrative reliefs. On the slopes of the hill, there are also stairways

linking the monument to the low-lying plain.

The monument's three divisions symbolize three stages of mental

preparation towards the ultimate goal according to the Buddhist

cosmology, namely Kāmadhātu (the world of desires), Rupadhatu

(the world of forms), and finally Arupadhatu (the formless world).

Kāmadhātu is represented by the base, Rupadhatu by the

five square platforms (the body), and Arupadhatu by the three

circular platforms and the large topmost stupa. The architectural

features between three stages have metaphorical differences. For

instance, square and detailed decorations in the Rupadhatu

disappear into plain circular platforms in the Arupadhatu to

represent how the world of forms – where men are still attached with

forms and names – changes into the world of the formless.

In 1885, a hidden structure under the base was accidentally

discovered.

The "hidden foot" contains reliefs, 160 of which are narrative

describing the real Kāmadhātu. The remaining reliefs are panels

with short inscriptions that apparently describe instruction for the

sculptors, illustrating the scene to be carved.

The real base is hidden by an encasement base, the purpose of which

remains a mystery. It was first thought that the real base had to be

covered to prevent a disastrous subsidence of the monument through the

hill.

There is another theory that the encasement base was added because the

original hidden foot was incorrectly designed, according to Vastu

Shastra, the Indian ancient book about architecture

and town planning.

Regardless of its intention, the encasement base was built with

detailed and meticulous design with aesthetics and religious compensation.

Reliefs

Borobudur contains approximately 2,670 individual bas reliefs (1,460 narrative and 1,212

decorative panels), which cover the façades and balustrades. The total relief surface is

2,500 square meters (26,909.8 sq ft) and they are distributed at the

hidden foot (Kāmadhātu) and the five square platforms (Rupadhatu).

The narrative panels, which tell the story of Sudhana

and Manohara,

are grouped into 11 series encircled the monument with the total length

of 3,000 meters (9,843 ft). The hidden foot contains the first series

with 160 narrative panels and the remaining 10 series are distributed

throughout walls and balustrades in four galleries starting from the

eastern entrance stairway to the left. Narrative panels on the wall read

from right to left, while on the balustrade read from left to right.

This conforms with pradaksina, the ritual of

circumambulation performed by pilgrims

who move in a clockwise direction while keeping the sanctuary

to their right.

The hidden foot depicts the workings of karmic law. The walls of the first gallery have two

superimposed series of reliefs; each consists of 120 panels. The upper

part depicts the biography of the Buddha, while the lower part

of the wall and also balustrades in the first and the second galleries

tell the story of the Buddha's former lives.

The remaining panels are devoted to Sudhana's further wandering about

his search, terminated by his attainment of the Perfect Wisdom.

- The law of karma (Karmavibhangga)

The 160 hidden panels do not form a continuous story, but each panel

provides one complete illustration of cause

and effect.

There are depictions of blameworthy activities, from gossip to murder,

with their corresponding punishments. There are also praiseworthy

activities, that include charity and pilgrimage to sanctuaries, and their

subsequent rewards. The pains of hell and the pleasure of heaven are

also illustrated. There are scenes of daily life, complete with the full

panorama of samsara (the

endless cycle of birth and death).

- The birth of Buddha (Lalitavistara)

Main article: The birth of Buddha

(Lalitavistara)

The story starts from the glorious descent of the Lord Buddha from

the Tushita

heaven, and ends with his first sermon in the Deer Park near Benares.[

The relief shows the birth of the Buddha as Prince Siddhartha, son of King Suddhodana and Queen Maya of Kapilavastu

(in present-day Nepal).

The story is preceded by 27 panels showing various preparations, in

heavens and on earth, to welcome the final incarnation of the Bodhisattva.

Before descending from Tushita heaven, the Bodhisattva entrusted his

crown to his successor, the future Buddha Maitreya.

He descended on earth in the shape of white elephants with six tusks,

penetrated to Queen Maya's right womb. Queen Maya had a dream of this

event, which was interpreted that his son would become either a

sovereign or a Buddha.

While Queen Maya felt that it was the time to give birth, she went to

the Lumbini

park outside the Kapilavastu city. She stood under a plaksa tree, holding one branch with her right

hand and she gave birth to a son, Prince Siddhartha. The story on the

panels continues until the prince becomes the Buddha.

- Prince Siddhartha story (Jataka) and other legendary persons (Avadana)

Jatakas are stories about the Buddha before he

was born as Prince Siddhartha.

Avadanas

are similar to jatakas, but the main figure is not the Bodhisattva

himself. The saintly deeds in avadanas are attributed to other legendary

persons. Jatakas and avadanas are treated in one and the same series in

the reliefs of Borobudur.

The first 20 lower panels in the first gallery on the wall depict the

Sudhanakumaravadana or the saintly deeds of Sudhana.

The first 135 upper panels in the same gallery on the balustrades are

devoted to the 34 legends of the Jatakamala.

The remaining 237 panels depict stories from other sources, as do for

the lower series and panels in the second gallery. Some jatakas stories

are depicted twice, for example the story of King Sibhi (Rama's

forefather).

- Sudhana's search for the Ultimate Truth (Gandavyuha)

Gandavyuha is the story told in the final chapter of the Avatamsaka Sutra about Sudhana's tireless wandering in search

of the Highest Perfect Wisdom. It covers two galleries (third and

fourth) and also half of the second gallery; comprising in total of 460

panels.

The principal figure of the story, the youth Sudhana, son of an

extremely rich merchant, appears on the 16th panel. The preceding 15

panels form a prologue to the story of the miracles during

Buddha's samadhi in the Garden of

Jeta at Sravasti.

During his search, Sudhana visited no less than 30 teachers but none

of them had satisfied him completely. He was then instructed by Manjusri

to meet the monk Megasri, where he was given the first doctrine. As his

journey continues, Sudhana meets (in the following order)

Supratisthita, the physician Megha (Spirit of Knowledge), the banker

Muktaka, the monk Saradhvaja, the upasika Asa (Spirit of Supreme Enlightenment),

Bhismottaranirghosa, the Brahmin Jayosmayatna, Princess Maitrayani, the monk

Sudarsana, a boy called Indriyesvara, the upasika Prabhuta, the banker

Ratnachuda, King Anala, the god Siva Mahadeva,

Queen Maya, Bodhisattva

Maitreya

and then back to Manjusri. Each meeting has given Sudhana a specific

doctrine, knowledge and wisdom. These meetings are shown in the third

gallery.

After the last meeting with Manjusri, Sudhana went to the residence

of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra; depicted in the fourth gallery.

The entire series of the fourth gallery is devoted to the teaching of

Samantabhadra. The narrative panels finally end with Sudhana's

achievement of the Supreme Knowledge and the Ultimate Truth.

Buddha statues

A Buddha statue with the hand position of dharmachakra mudra (turning the Wheels of

the Law).

Apart from the story of Buddhist cosmology carved in stone, Borobudur has many

statues of various Buddhas. The cross-legged statues are seated in a lotus position and distributed on the five square

platforms (the Rupadhatu level) as well as on the top platform

(the Arupadhatu level).

The Buddha statues are in niches at the Rupadhatu level,

arranged in rows on the outer sides of the balustrades, the number of

statues decreasing as platforms progressively diminish to the upper

level. The first balustrades have 104 niches, the second 104, the third

88, the fourth 72 and the fifth 64. In total, there are 432 Buddha

statues at the Rupadhatu level.

At the Arupadhatu level (or the three circular platforms),

Buddha statues are placed inside perforated stupas. The

first circular platform has 32 stupas, the second 24 and the third 16,

that add up to 72 stupas.

Of the original 504 Buddha statues, over 300 are damaged (mostly

headless) and 43 are missing (since the monument's discovery, heads have

been stolen as collector's items, mostly by Western museums).

At glance, all the Buddha statues appear similar, but there is a

subtle difference between them in the mudras

or the position of the hands. There are five groups of mudra:

North, East, South, West and Zenith, which represent the five cardinal

compass points according to Mahayana.

The first four balustrades have the first four mudras: North,

East, South and West, of which the Buddha statues that face one compass

direction have the corresponding mudra. Buddha statues at the

fifth balustrades and inside the 72 stupas on the top platform have the

same mudra: Zenith. Each mudra represents one of the Five Dhyani Buddhas; each has its own symbolism.

They are Abhaya mudra for Amoghasiddhi

(north), Vara mudra for Ratnasambhava

(south), Dhyana mudra for Amitabha (west), Bhumisparsa mudra for Aksobhya (east) and Dharmachakra mudra for Vairochana (zenith).

Restoration

Borobudur attracted attention in 1885, when Yzerman, the Chairman of

the Archaeological Society in Yogyakarta, made a discovery about the hidden

foot.

Photographs that reveal reliefs on the hidden foot were made in

1890–1891.

The discovery led the Dutch East Indies government to take steps to

safeguard the monument. In 1900, the government set up a commission

consisting of three officials to assess the monument: Brandes, an art

historian, Theodoor van Erp, a Dutch army engineer officer, and Van de Kamer, a

construction engineer from the Department of Public Works.

In 1902, the commission submitted a threefold plan of proposal to the

government. First, the immediate dangers should be avoided by resetting

the corners, removing stones that endangered the adjacent parts,

strengthening the first balustrades and restoring several niches,

archways, stupas and the main dome. Second, fencing off the courtyards,

providing proper maintenance and improving drainage by restoring floors

and spouts. Third, all loose stones should be removed, the monument

cleared up to the first balustrades, disfigured stones removed and the

main dome restored. The total cost was estimated at that time around

48,800 Dutch guilders.

The restoration then was carried out between 1907 and 1911, using the

principles of anastylosis and led by Theodor van Erp.

The first seven months of his restoration was occupied with excavating

the grounds around the monument to find missing Buddha heads and panel

stones. Van Erp dismantled and rebuilt the upper three circular

platforms and stupas. Along the way, Van Erp discovered more things he

could do to improve the monument; he submitted another proposal that was

approved with the additional cost of 34,600 guilders. At first glance

Borobudur had been restored to its old glory.

Due to the limited budget, the restoration had been primarily focused

on cleaning the sculptures, and Van Erp did not solve the drainage

problem. Within fifteen years, the gallery walls were sagging and the

reliefs showed signs of new cracks and deterioration.

Van Erp used concrete from which alkali salts and calcium hydroxide leached and were transported into the

rest of the construction. This caused some problems, so that a further

thorough renovation was urgently needed.

Small restorations have been performed since then, but not sufficient

for complete protection. In the late 1960s, the Indonesian

government had requested from the international community a major

renovation to protect the monument. In 1973, a master plan to restore

Borobudur was created.

The Indonesian government and UNESCO

then undertook the complete overhaul of the monument in a big

restoration project between 1975–1982.

The foundation was stabilized and all 1,460 panels were cleaned. The

restoration involved the dismantling of the five square platforms and

improved the drainage by embedding water channels into the monument.

Both impermeable and filter layers were added. This colossal project

involved around 600 people to restore the monument and cost a total of US$

6,901,243.

After the renovation was finished, UNESCO listed Borobudur as a World Heritage Site in 1991. It is listed under Cultural criteria (i) "to represent a masterpiece of

human creative genius", (ii) "to exhibit an important interchange of

human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the

world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts,

town-planning or landscape design", and (vi) "to be directly or tangibly

associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with

beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal

significance".[3]

Gallery of reliefs

|

The Apsara of Borobudur.

|

|||

Borobudur Temple is one of the historical legacy must be guarded..^^

ReplyDeleteyes i think so. it has been doing by our government. let's vivit yogyakarta, and you will get unforgettable experience.

ReplyDeletemarvellous !!!..

ReplyDeletethe big temple in the world